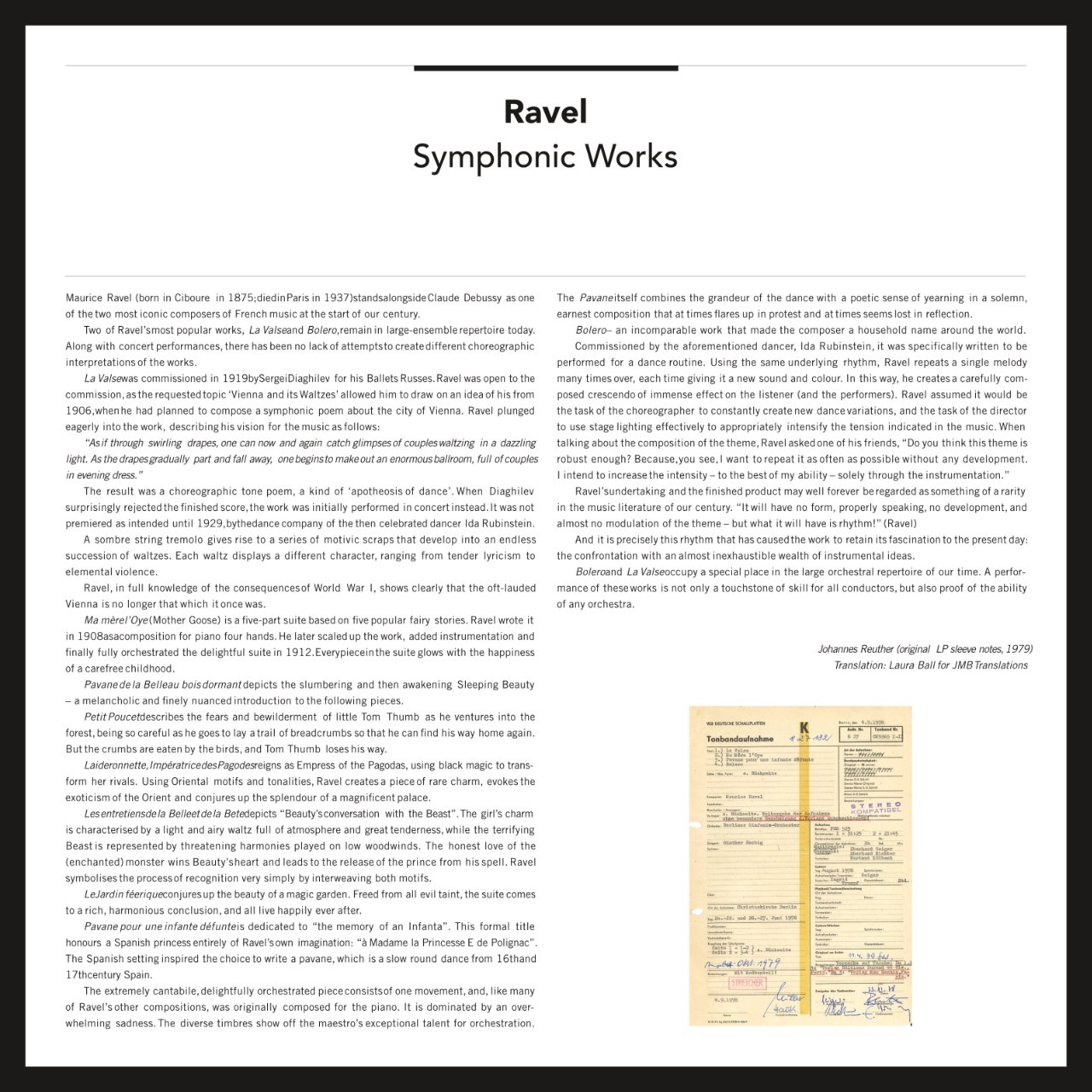

Maurice Ravel

La Valse - Ma Mère L’oye -

Pavane Pour Une Infante Défunte - Bolero

Berliner Sinfonie-Orchester - Günther Herbig

Maurice Ravel (born in Ciboure in 1875; died in Paris in 1937) stands alongside Claude Debussy as one of the two most iconic composers of French music at the start of our century.

Two of Ravel’s most popular works, La Valse and Bolero, remain in large-ensemble repertoire today. Along with concert performances, there has been no lack of attempts to create different choreographic interpretations of the works.

La Valse was commissioned in 1919 by Sergei Diaghilev for his Ballets Russes. Ravel was open to the commission, as the requested topic ‘Vienna and its Waltzes’ allowed him to draw on an idea of his from 1906, when he had planned to compose a symphonic poem about the city of Vienna. Ravel plunged eagerly into the work, describing his vision for the music as follows:

“As if through swirling drapes, one can now and again catch glimpses of couples waltzing in a dazzling light. As the drapes gradually part and fall away, one begins to make out an enormous ballroom, full of couples in evening dress.”

The result was a choreographic tone poem, a kind of ‘apotheosis of dance’. When Diaghilev surprisingly rejected the finished score, the work was initially performed in concert instead. It was not premiered as intended until 1929, by the dance company of the then celebrated dancer Ida Rubinstein.

A sombre string tremolo gives rise to a series of motivic scraps that develop into an endless succession of waltzes. Each waltz displays a different character, ranging from tender lyricism to elemental violence.

Ravel, in full knowledge of the consequences of World War I, shows clearly that the oft-lauded Vienna is no longer that which it once was.

Ma mère l’Oye (Mother Goose) is a five-part suite based on five popular fairy stories. Ravel wrote it in 1908 as a composition for piano four hands. He later scaled up the work, added instrumentation and finally fully orchestrated the delightful suite in 1912. Every piece in the suite glows with the happiness of a carefree childhood.

Pavane de la Belle au bois dormant depicts the slumbering and then awakening Sleeping Beauty – a melancholic and finely nuanced introduction to the following pieces.

Petit Poucet describes the fears and bewilderment of little Tom Thumb as he ventures into the forest, being so careful as he goes to lay a trail of breadcrumbs so that he can find his way home again. But the crumbs are eaten by the birds, and Tom Thumb loses his way.

Laideronnette, Impératrice des Pagodes reigns as Empress of the Pagodas, using black magic to transform her rivals. Using Oriental motifs and tonalities, Ravel creates a piece of rare charm, evokes the exoticism of the Orient and conjures up the splendour of a magnificent palace.

Les entretiens de la Belle et de la Bete depicts “Beauty’s conversation with the Beast”. The girl’s charm is characterised by a light and airy waltz full of atmosphere and great tenderness, while the terrifying Beast is represented by threatening harmonies played on low woodwinds. The honest love of the (enchanted) monster wins Beauty’s heart and leads to the release of the prince from his spell. Ravel symbolises the process of recognition very simply by interweaving both motifs.

Le Jardin féerique conjures up the beauty of a magic garden. Freed from all evil taint, the suite comes to a rich, harmonious conclusion, and all live happily ever after.

Pavane pour une infante défunte is dedicated to “the memory of an Infanta”. This formal title honours a Spanish princess entirely of Ravel’s own imagination: “à Madame la Princesse E de Polignac”. The Spanish setting inspired the choice to write a pavane, which is a slow round dance from 16th and 17th century Spain.

The extremely cantabile, delightfully orchestrated piece consists of one movement, and, like many of Ravel’s other compositions, was originally composed for the piano. It is dominated by an overwhelming sadness. The diverse timbres show off the maestro’s exceptional talent for orchestration. The Pavane itself combines the grandeur of the dance with a poetic sense of yearning in a solemn, earnest composition that at times flares up in protest and at times seems lost in reflection.

Bolero – an incomparable work that made the composer a household name around the world.

Commissioned by the aforementioned dancer, Ida Rubinstein, it was specifically written to be performed for a dance routine. Using the same underlying rhythm, Ravel repeats a single melody many times over, each time giving it a new sound and colour. In this way, he creates a carefully composed crescendo of immense effect on the listener (and the performers). Ravel assumed it would be the task of the choreographer to constantly create new dance variations, and the task of the director to use stage lighting effectively to appropriately intensify the tension indicated in the music. When talking about the composition of the theme, Ravel asked one of his friends, “Do you think this theme is robust enough? Because, you see, I want to repeat it as often as possible without any development. I intend to increase the intensity – to the best of my ability – solely through the instrumentation.”

Ravel’s undertaking and the finished product may well forever be regarded as something of a rarity in the music literature of our century. “It will have no form, properly speaking, no development, and almost no modulation of the theme – but what it will have is rhythm!” (Ravel)

And it is precisely this rhythm that has caused the work to retain its fascination to the present day: the confrontation with an almost inexhaustible wealth of instrumental ideas.

Bolero and La Valse occupy a special place in the large orchestral repertoire of our time. A performance of these works is not only a touchstone of skill for all conductors, but also proof of the ability of any orchestra.

Johannes Reuther (Original LP sleeve notes, 1979)

Translation: Laura Ball for JMB Translations

Encounter with an enchanted world

It would have been easy to give this text the title “In search of lost sound”, now that the composite sound of the master tape, as it was called into being by the conductor, is being made audible again. But that would be to forget that this recording from almost four decades ago had enjoyed quite a demand on the record market, gone through various reissues and on account of this success was never truly “perdu” in the Proustian sense. With its excursion into the magically enchanted music of Maurice Ravel, the Berlin Symphony Orchestra (BSO) cut its first discs of French repertoire, which this capital-city orchestra founded in 1952 had certainly never ignored in its concert scheduling, yet had not recorded before.

One limiting factor was the general shortage of hard currency, restricting the availability of music scores from publishers in the West. However, the BSO was given the chance to enhance its media profile. Günther Herbig knew the Berlin Symphony Orchestra well, even before being made Principal Conductor in 1977 of what is now the Konzerthaus orchestra. He had deputized in that post from 1966 to 1972 and remained a welcome guest even after assuming the direction of the Dresden Philharmonic in 1972. Herbig used the two years or more of negotiations before his assumption of office in Berlin in September ’77 not only to further increase the number of musicians in the ensemble but also to obtain a written agreement entitled “Entwicklungsperspektive BSO” (development prospects for the BSO), which envisaged a more substantial presence for the orchestra in broadcasts and on gramophone records. Accordingly, the works Herbig recorded for ETERNA included a Brahms cycle, modern classics such as Shostakovich, works of the Second Viennese School, and music from the field of Romance language and culture.

As there was no dedicated concert hall for a long time, the recordings were made in the familiar atmosphere of the Christuskirche in Oberschöneweide. Built to plans by Robert Leibnitz and dedicated in 1908, the church has moderate dimensions untypical of its period and possesses excellent acoustics. The intimacy of a chamber orchestra has been and continues to be as readily available as the exquisitely blended sounds of late Romantic scores; in those days, the reverberation time was reduced by hanging shrouds over the galleries. A creative approach to placement of the musicians was necessary when large orchestral forces were deployed. For this recording, as the long-serving BSO cellist Jürgen Kögel recalls, Herbig did not place the musicians with their backs to the altar as was customary but in front of one of the side aisles. This made better use of the nicely balanced instrumentation, and even the opulent scoring of such works as La valse had “room to breathe” in this fanned-out seating arrangement. This illustrated Herbig’s “particularly sensitive ear for sound and intonation”, Kögel continues. His colleague Christian Lucass, who by then had been leader of the second violins for many years, emphasizes that Herbig “rehearsed in his usual thorough manner: his rehearsal technique was meticulous”, and so he knew how to achieve “the necessary diffuse colours” that form part of the idiom of certain works. Solo flautist Richard Waage, an orchestra member from 1961 to 2002, also valued the work ethic of his Principal Conductor – notably when it came to the execution of solo parts. “With Herbig things were ‘more open’, when you had worked your way into a certain context, than with other conductors. He allowed you more freedom. You could offer more as an individual. I liked that a lot.” On one occasion when he had the opportunity to see Herbig’s conducting score, he was impressed by how every harmonic step was marked, so that the score bore traces of a musicological analysis. “This was the mathematical impulse” characteristic, he judged, of Herbig’s way of working.

This architectural, formally structured approach to the music fitted well with the recording technique of those days, which did not allow breakdown into such small steps as today. Arches of tension thus sound more plausible, because there are fewer pieces to put together. “When you have long takes, of course that makes it all more organic,” concludes Richard Waage. It will surely have been these working conditions and the conductor’s specific style that made it possible, even in such an unpretentious piece as the Pavane, “to bring out the character of mourning”, which so moved Jürgen Kögel and other participants.

Dirk Stöve

Translation: Janet and Michael Berridge, London

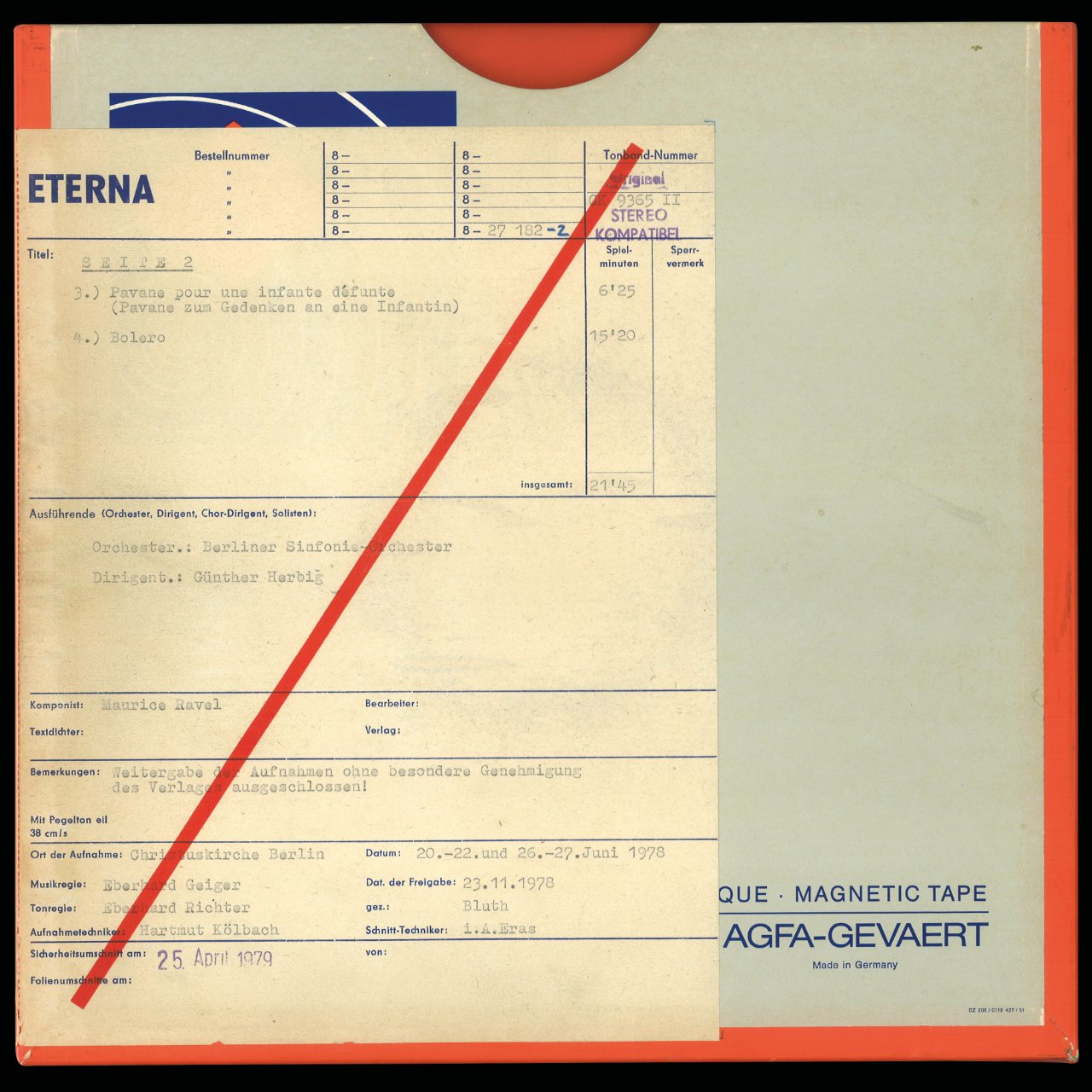

Label: Eterna

Studio Master Copy

master tape order number: HH01.00.231

595,- €

Valid for all countries

2 metal reels

Horch House Deluxe Packaging

Standard Master Copy

master tape order number: HH05.00.231

480,- €

Valid for all countries

1 metal reel

Horch House Deluxe Packaging

Pure Master Copy

master tape order number: HH03.00.231

325,- €

Valid for all countries

1 plastic reel

Special Archive Box

Studio Master Copy (Packaging example)

Order number: HH01.00.XXX

Tape Material: RTM SM900

Recording Speed: 15IPS-38cm/sec-510 nWb/m

Equalization: CCIR

Width & tracks: 1/4” - 2 Track

Reels: Metal - 10.5“ - 26,5 cm Packaging: Horch House Deluxe

Standard Master Copy (Packaging example)

Order number: HH05.00.XXX

Tape Material: RTM LPR90

Recording Speed: 15IPS-38cm/sec-320 nWb/m

Equalization: CCIR

Width & tracks: 1/4” - 2 Track

Reels: Metal - 10.5“ - 26,5 cm

Packaging: Horch House Deluxe

Pure Master Copy (Packaging example)

Order number: HH03.00.XXX

Tape Material: RTM LPR90

Recording Speed: 15IPS-38cm/sec-320 nWb/m

Equalization: CCIR

Width & tracks: 1/4” - 2 Track

Reels: Plastic - 10.5“ - 26,5 cm

Packaging: Special Archive Box