Image 1 of 9

Image 1 of 9

Image 2 of 9

Image 2 of 9

Image 3 of 9

Image 3 of 9

Image 4 of 9

Image 4 of 9

Image 5 of 9

Image 5 of 9

Image 6 of 9

Image 6 of 9

Image 7 of 9

Image 7 of 9

Image 8 of 9

Image 8 of 9

Image 9 of 9

Image 9 of 9

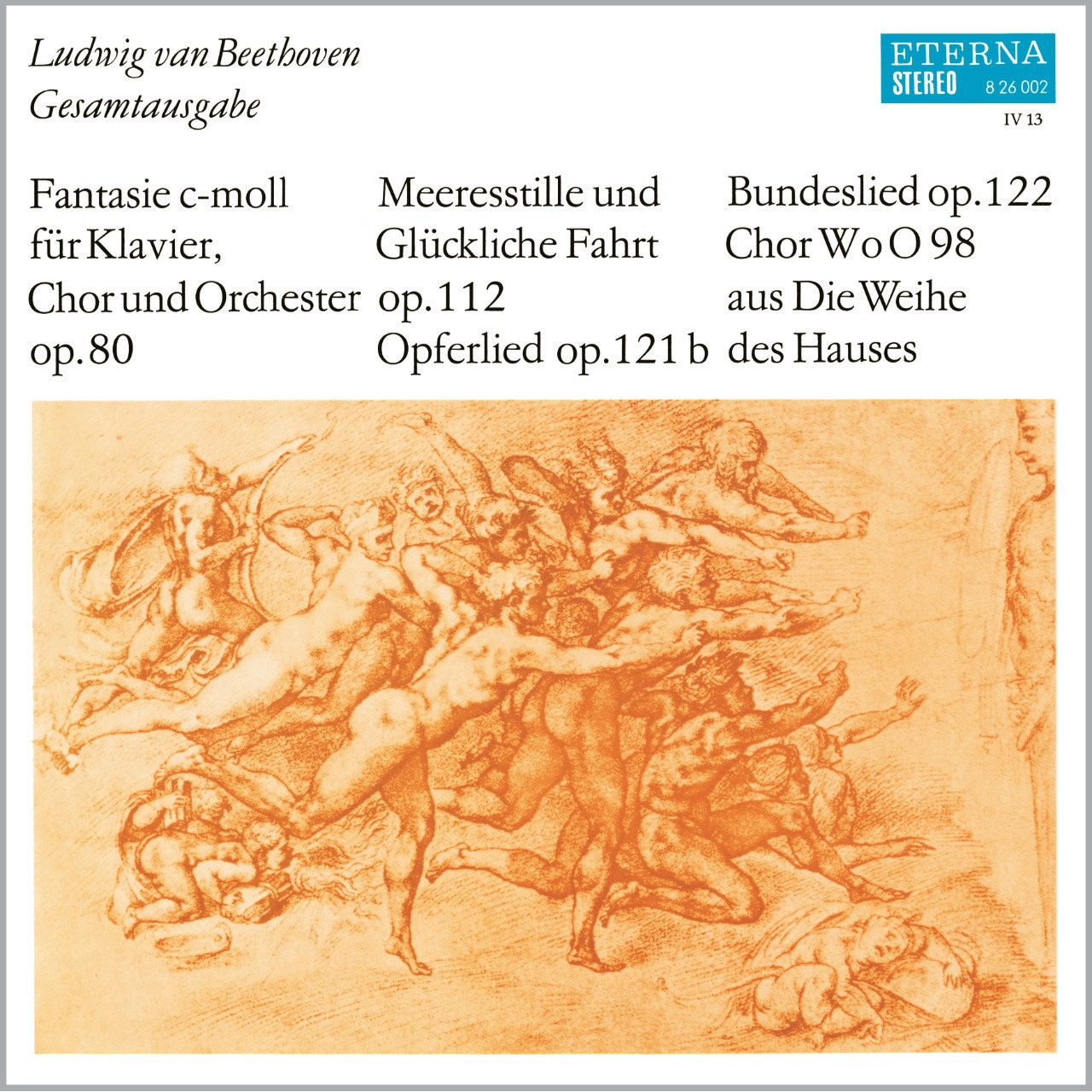

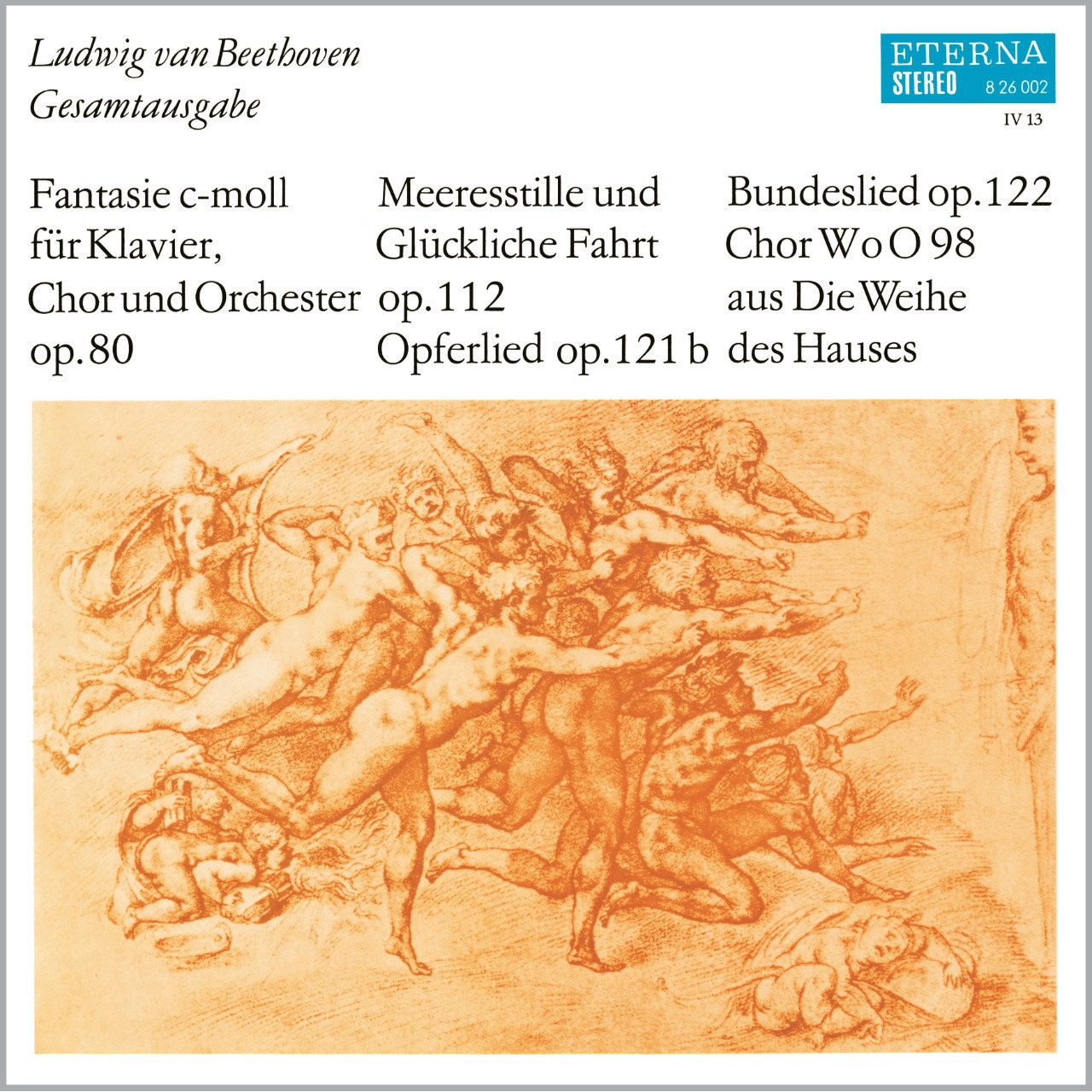

Ludwig Van Beethoven - Gesamtausgabe

Sales Prices for Germany incl. 19% sales tax (VAT)

Pure Master: 325,00 €

Standard Master: 480,00 €

Studio Master: 595,00 €

Prices for other EU Countries calculated at checkout before purchase.

Prices outside EU Countries excluding VAT.

Sales Prices for Germany incl. 19% sales tax (VAT)

Pure Master: 325,00 €

Standard Master: 480,00 €

Studio Master: 595,00 €

Prices for other EU Countries calculated at checkout before purchase.

Prices outside EU Countries excluding VAT.

Sales Prices for Germany incl. 19% sales tax (VAT)

Pure Master: 325,00 €

Standard Master: 480,00 €

Studio Master: 595,00 €

Prices for other EU Countries calculated at checkout before purchase.

Prices outside EU Countries excluding VAT.

-

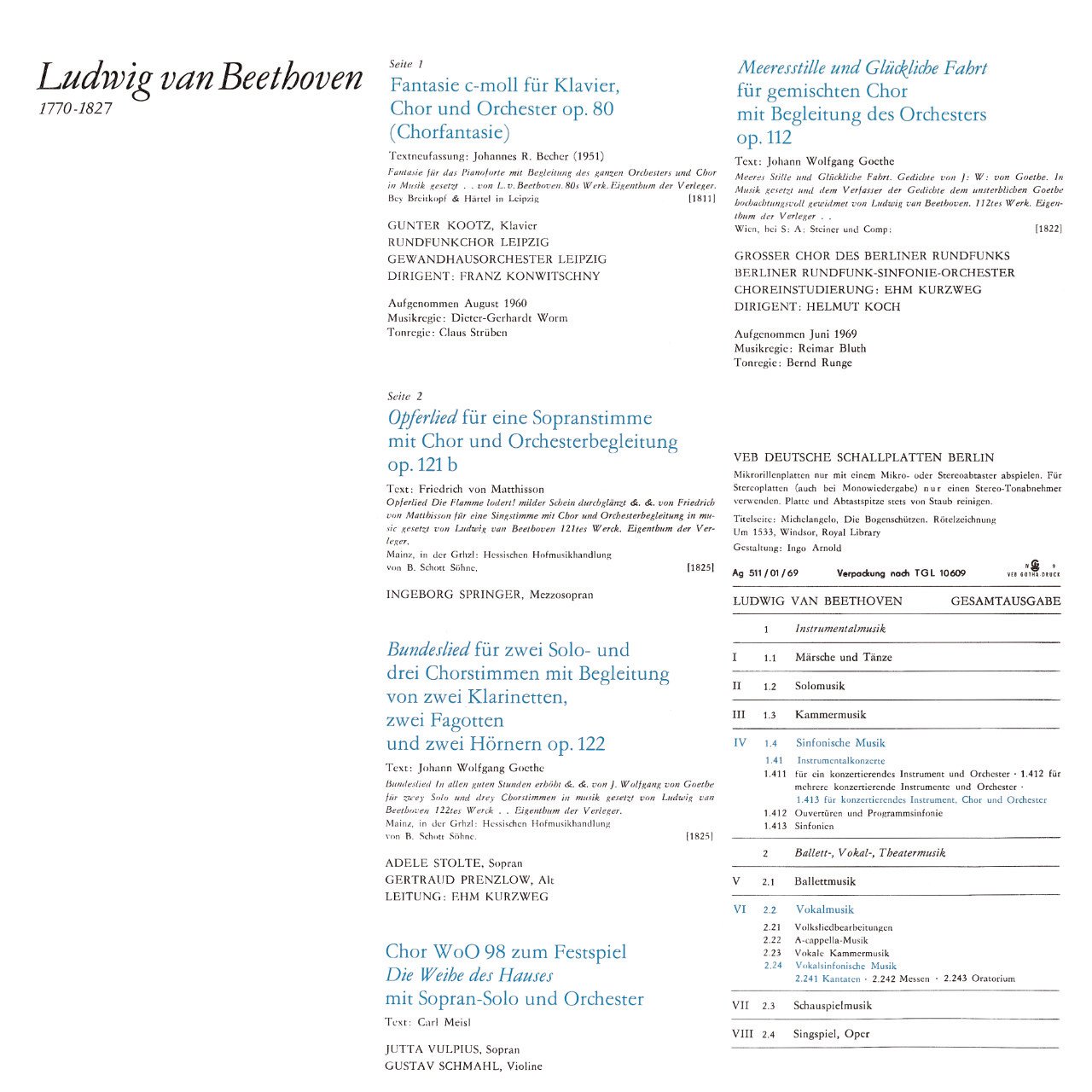

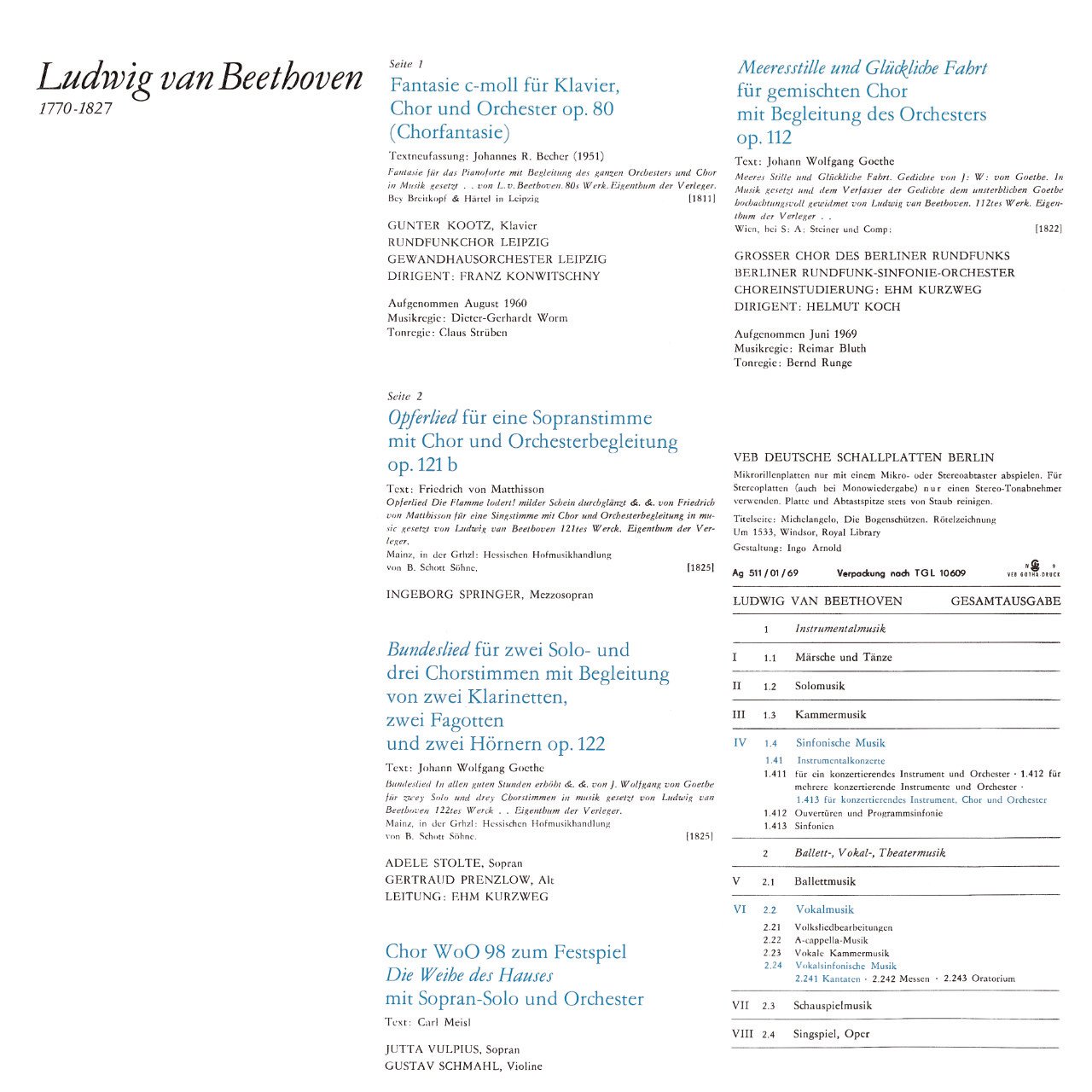

The Choral Fantasia op. 80 stands alone among Beethoven's works for large forces. Only the piano introduction is strictly speaking a "fantasia"; then the familiar song melody begins in the piano and is subjected to eight variations in which the orchestra takes part before at last being taken up by the chorus. Is it therefore a piano concerto with closing chorus? No, it lacks the usual concerto form. Is it a cantata? No, the preceding sections for piano and orchestra are too extensive and weighty. So it is neither the one nor the other but contains a bit of each! Even the ternary conception of the piano concertos can be discerned, since the introduction - the true "fantasia" - is without question to be seen as an independent movement. (Beethoven in fact added it later; in the memorable "academy" of December 1808, when he presented the work together with the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, he improvised that movement on the unaccompanied piano, and his written version still sounds like an improvisation.)

The ternary structure of the following variations clearly indicates the intention of a middle movement. The variations are sometimes connected with one another by means of short, thoughtful development sections instead of simply being presented in mechanical order, and even in the first four variations, which do simply follow one another, a self-contained chain of ideas is present.

The song melody is initially sung by soloists before being gently modified by the solo flute and then in the shawm-like tones of pairs of oboes and clarinets. There follows a chamber-music variation in the (prescribed) string quartet, and only then does the dominant theme appear unchanged in a jubilant orchestral tutti. Coming after the dark dramatic introduction, this

"Arcadian" thematic procession can without question only be understood programmatically.

The two conflicting sides also collide into one another in the ensuing variations. The dramatic minor-key variation C minor) is followed by the heroic idyll of the large Adagio variation (A major) and the warlike march variation (F major). And only after an elegiac return to the gloomy initial state and an Arcadian welcome by the "shawms" is the beautiful song melody heard in the human voices. The last part, the "Finale", elevates the work to a cantata. Words are at last permissible.

But what does the chorus sing? Nobody can fail to hear the unmistakable similarity to the Ode to Joy theme in the Ninth Symphony Beethoven wrote fifteen years later; syllable for syllable, the song melody seems to fit Schiller's text like a glove, yet the text to which Beethoven composed the Choral Fantasia was one ordered for the purpose at the last minute. We know that he did not conceive the work around that text, for he only received it when he was about to start writing the third movement. Nor does it help to point out that the melody already showed up in

Beethoven's earlier song "Gegenliebe" (Bürger), with its striking declamatory irregularities which suggest that he had actually composed the melody for a quite different text at an even earlier stage. The original text could have been Schiller's Ode to Joy, and there do seem to be reasons why he might not have wanted to publish a work containing that text at the time. At any rate, it is probably not wrong to see in the Choral Fantasia the forerunner of the Ninth Symphony, but it was intended as an independent, unique work, and does not represent a "study" or "preliminary stage".

Beethoven himself expressed dissatisfaction with the text of the Choral Fantasia, and explicitly asked his Leipzig publisher to produce a more suitable one. His only proviso was that the word

"Kraft" retain its position near the end.

Beethoven's wish was not fulfilled until the middle of the twentieth century, when with a sure feel for the importance of what he was doing, the socialist poet Johannes R. Becher produced a new text to fit the music. Out of misplaced respect for its weak text, the bourgeoisie denied Beethoven's large-scale work, which steers towards the Ninth Symphony, the acclaim due to it. With Becher's appropriate stanzas, the work established itself as an indispensable cultural asset of the German Democratic Republic at the World Festival of Youth in Berlin in 1951.

It is in the nature of the other choral works with orchestra presented on this record that they link up without difficulty to the ethos of the Choral Fantasia. Even if we did not keep to the order in which they are presented, the Opferlied would deserve first mention, since Matthisson's poem had haunted Beethoven ever since 1796, when he set "Adelaide", likewise by Matthisson, whom he admired. "For him it seems to have been a prayer through all the ages" (Nottebohm). He loved nothing better than the end of the second stanza, where "beauty" and "goodness" are coupled. He often turned the thought into musical mottoes which he gave to friends and visitors.

The marked Classicist conception (female pre-centor with choir) corresponds with the formally perfect linear structure of the parts and the strict reserve in the harmonic sequences. What the parts - vocal and instrumental - have to present here "with fervent, devout feeling" was more than just a prayer; it was the solemn disclosure of Beethoven's maxims regarding life and art.

The Bundeslied may be seen as the cheerfully convivial counterpart of the Opferlied. Beethoven published both together as op. 121[b] and op. 122 in the summer of 1825. A publishing journal in Mainz wrote at the time: "The present work shows how deeply Beethoven empathized with Goethe. Goethe would express the present poem in music in just this way if he were as great a composer as he is a poet."

There is nothing to add to that apt observation even today, unless it be to mention the almost perfect match between syllables and melody throughout - another aspect which links the Bundeslied with the Ode to Joy theme in the Ninth Symphony. Here too, the song becomes the basic idea of the community. Even the obbligato woodwind parts following the vocal lines were included in the choral finale of the Ninth. The rapidly following pairs of instruments (clarinets, bassoons and horns) lend the Bundeslied a convivial colouring of its very own, which is particularly beautiful in the interludes and at the end.

Beethoven was less fortunate in the festival chorus to The Consecration of the House, which was performed, together with that far more outstanding overture and other borrowed pieces, for the inauguration in 1822 of the new theatre in the Josefstadt with which he was connected. But even in that chorus, his masterly hand is unmistakably evident, particularly in the noble merging of the soprano solo with the violin cantilena, "a scene of beautified life".

A few years after writing the incidental music to Egmont, Beethoven combined Goethe's poems Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage into a small cantata, which he sent to the poet with a gushing dedication after its publication in 1822. The cantata had actually been written during the first months of the Congress of Vienna (1814/15), a period which speaks for itself. Beethoven would hardly have set the two poems for such ambitious forces if his sole intention had been to musically depict scenes in nature. Goethe's purpose was also more than to merely write superficial nature poetry when he saw the leaden motionlessness of the sea, "the deathly silence fearsome" divided by the winds, the fog disperse and the distant land draw nearer. The political Beethoven understood this symbolism more narrowly. To his regret, however, he had to pay dearly for his illusion, for the leaden calm set in more strongly than ever after the victories of the nations over Napoleon. When the first fog at last dispersed, Beethoven was no longer among the living.

Coming at a time when no "land" was in sight, his dedication to the "national poet" was prophetic, a nationalistically revolutionary appeal on the part of the composer to the poet. Was it this admonition which Goethe felt to be pointed? At any rate, he refrained from thanking Beethoven for setting his two epigrams in a cantata so loaded with meaning.

Harry Goldschmidt (1970)

Translation: J & M Berridge

Label: Eterna

-

01 Fantasie c-moll op.80

02 Meeresstille und Glückliche Fahrt op.112

03 Opferlied op.121b

04 Bundeslied op.122

05 Die Weihe des Hauses -

Pure Master Product Configuration:

1/4” - 2 Track RTM LPR90 - 15IPS - 38cm/sec - CCIR - 320 nWb/m - 1 Plastic Reel(s) - Special Archive Box(es)

Standard Master Product Configuration:

1/4” - 2 Track RTM LPR90 - 15IPS - 38cm/sec - CCIR - 320 nWb/m - 1 Metal Reel(s) - Special Archive Box(es) - Horch House Deluxe Packaging

Studio Master Product Configuration:

1/4” - 2 Track RTM SM900 - 15IPS - 38cm/sec - CCIR - 510 nWb/m - 2 Precision Metal Reel(s) - Special Archive Box(es) - Horch House Deluxe Packaging